Given the North American love of television, it is not hyperbole to say this revolution has had a notable effect on our lives, our culture and our identities. It is strange to consider that we might owe a great deal of these cultural changes to the work of a single X-Men comics writer.

This writer played a significant role in developing the long-form storytelling techniques that have since found their way into everything from Buffy the Vampire Slayer to Game of Thrones to Stranger Things.

In the 1960s, X-Men comics were a failure for Marvel, despite boasting the creative pairing of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. After 63 issues, the series was effectively cancelled and left in limbo for five years. Then in 1975, a 24 year old editorial assistant named Chris Claremont took over as the new writer of X-men.

|

| The First Issue of X-Men. |

In that time, X-Men went from a B-list title to the best-selling comic book in the world, and Claremont holds the Guinness World Record to this day for the bestselling single issue comic of all-time: X-Men (vol 2) #1.

All of this is established comics history. What does it have to do with television?

A seismic shift: Casual to dedicated audiences

By the late 1990s, television had begun a transition. According to culuralist Jimmie Reeves and his colleagues, TV started “programming forms that inspire devoted rather than casual engagement.” Prior to this, TV was dependant on broadcast scheduling and had to be designed to be accessible to casual viewers. This was simply because there was no way to guarantee audiences would be in front of their television the next week at the exact same time to see the next episode.With the rise of VHS or DVD boxed sets, personal video recorders and later, streaming services, television was set free to use long-form continuity-based storytelling. Those stories featured more complex character dynamics within more continuous, open-ended plots and structures.

As a result of this transition, the way most of the globe consumed television changed within a very short period of time. This shift led us from self-contained, non-continuous stories to the very concept of being “binge-worthy.”

This same type of transition is exactly what Claremont contributed to comics, decades prior.

When Claremont started on X-Men in 1975, comics were also written for a casual audience. Stan Lee is famously quoted as saying: “Every comic book is someone’s first.” Casual engagement needed to be woven into the books. That was the status quo and creators were not allowed to drift too far from it.

But Claremont was not interested in telling the same stories over and over, and because he wrote X-Men for 16 years, he covered a lot of stories. This necessitated a new approach to writing, one that allowed for change: new characters and new directions. In light of this, Claremont’s X-Men were constantly changing and growing in a way that did not conform to Stan Lee’s mandate.

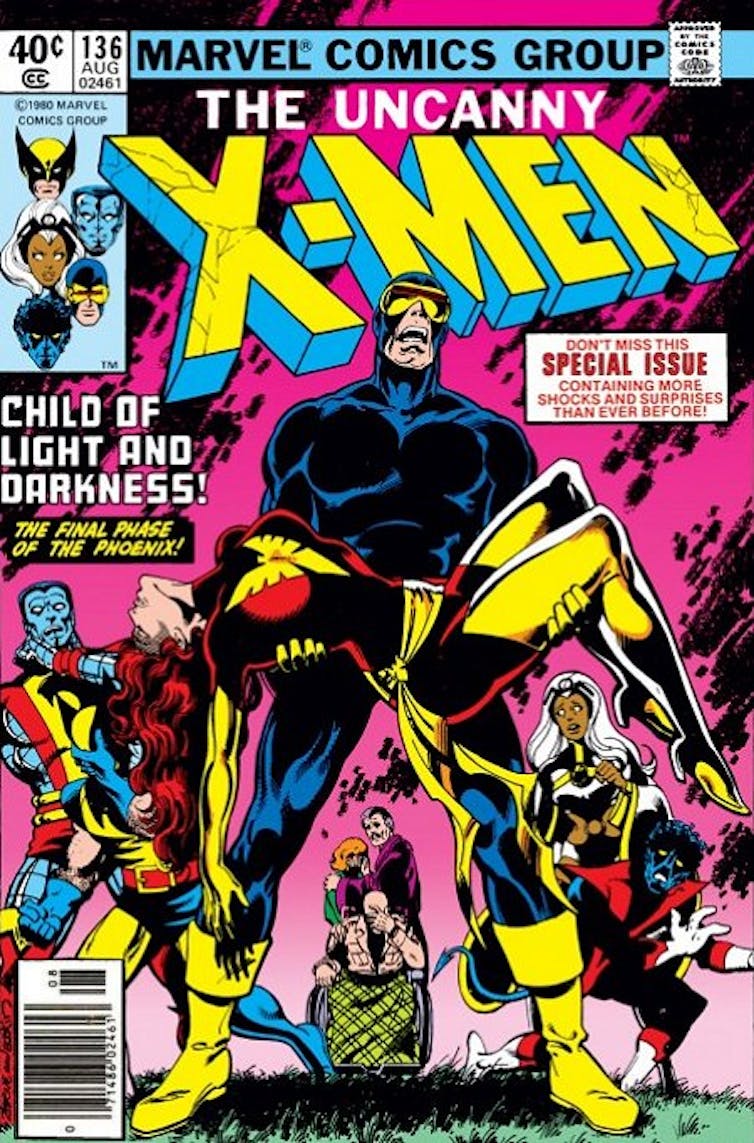

|

| X-Men #136 |

If these elements sound familiar, they should. Most of our current television programs use the same components to build their devoted followings.

From Kitty to Buffy

The most direct successor of Claremont’s work is Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer. According to cultural critic Geoff Klock, Claremont’s influence “looms too large for many to see. A lot of folks don’t know that Joss Whedon would not have created Buffy or Angel were it not for Claremont’s X-men.”

The same can be said for an entire season of Whedon’s Angel, which used Claremont’s Illyana Rasputin character as the basis for a long arc about Angel’s son, Connor. Whedon is quite open about how Claremont inspired him, and Buffy is frequently cited as a touchstone moment in the development of long-form storytelling in television.

A broader absorption

Beyond this direct influence, Claremont’s techniques are widely visible among the best-loved television series within this current golden age: nested story structures, drawn-out mysteries, character melodrama and dysfunctional collectives that have to put aside their differences to defeat a common foe.The only thing missing is the yellow tights. Perceived as a whole, Claremont’s work constructed a sort of long-form storytelling toolbox, one that our TV creators have been dipping into ever since.

In the end

When Claremont was finally pushed out of X-Men comics, he was the No. 1 comics writer in the world.He wasn’t pushed out because he was failing at his job, but because he refused to comply with an editorial mandate that requested a return to status quo, to casual engagement all over again.

His greatest accomplishment — developing ways by which a character-based story could unfold slowly over time — was, ironically, what cost him his job. But if our current television landscape is any indication, our culture has profited greatly from the choices Claremont made, and from the ingenuity that followed those choices.

About Today's Contributor:

J. Andrew Deman,, Professor, University of Waterloo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Cargo is worth watching, particularly for fans of horror cinema, but its aesthetic will be best served, I suspect, by the small screen.

Cargo is worth watching, particularly for fans of horror cinema, but its aesthetic will be best served, I suspect, by the small screen.