|

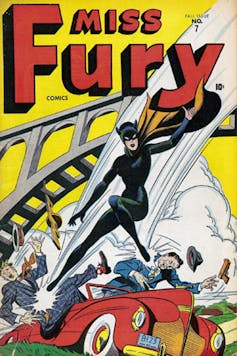

| Miss Fury had cat claws, stiletto heels and a killer make-up compact. (Author provided) |

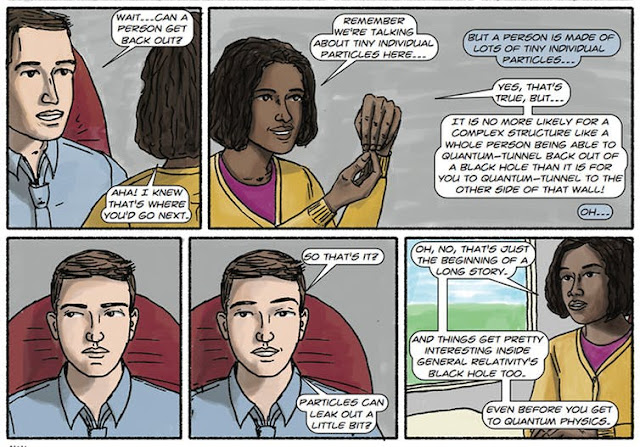

Miss Fury’s creator – whose real name was June – shared much of the gritty ingenuity of her superheroine. Like other female artists of the Golden Age, Mills was obliged to make her name in comics by disguising her gender. As she later told the New York Post, “It would have been a major let-down to the kids if they found out that the author of such virile and awesome characters was a gal.”

|

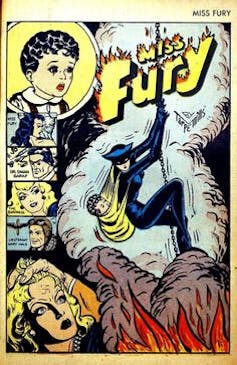

| Miss Fury (Author provided) |

Comics then and now tend to feature weak-kneed female characters who seem to exist for the sole purpose of being saved by a male hero – or, worse still, are “fridged”, a contemporary comic book colloquialism that refers to the gruesome slaying of an undeveloped female character to deepen the hero’s motivation and propel him on his journey.

But Mills believed there was room in comics for a different kind of female character, one who was able, level-headed and capable, mingling tough-minded complexity with Mills’ own taste for risqué behaviour and haute couture gowns.

|

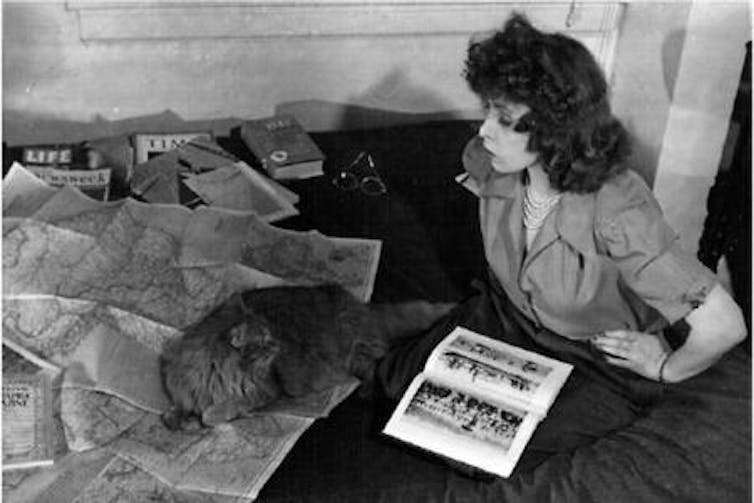

| Tarpe Mills was obliged to make her name in comics during the 1940s by disguising her gender. (Author provided) |

|

| A WW2 plane featuring an image of Miss Fury. (Image via tarpemills.com) |

Miss Fury ran a full decade from April 1941 to December 1951, was syndicated in 100 different newspapers at the height of her wartime fame, and sold a million copies an issue in reprints released by Timely (now Marvel) comics.

Pilots flew bomber planes with Miss Fury painted on the fuselage. Young girls played with paper doll cut outs featuring her extensive high fashion wardrobe.

An anarchic, ‘gender flipped’ universe

Miss Fury’s “origin story” offers its own coolly ironic commentary on the masculine conventions of the comic genre. |

| Miss Fury (Author provided) |

On the way to the ball, Marla takes on a gun-toting killer, using her cat claws, stiletto heels, and – hilariously – a puff of powder blown from her makeup compact to disarm the villain. She leaves him trussed up with a hapless and unconscious police detective by the side of the road.

This was an anarchic, gender flipped, comic book universe in which the protagonist and principle antagonists were women, and in which the supposed tools of patriarchy – high heels, makeup and mermaid bottom ball gowns – were turned against the system. Arch nemesis Erica Von Kampf – a sultry vamp who hides a swastika-branded forehead behind a v-shaped blond fringe – also displayed amazing enterprise in her criminal antics.

|

| Miss Fury (Author provided) |

By contrast, the female characters possessed a gritty ingenuity inspired by Noir as much as by the changed reality of women’s wartime lives. Half way through the series, Marla got a job, and – astonishingly, for a Sunday comic supplement – became a single mother, adopting the son of her arch nemesis, wrestling with snarling dogs and chains to save the toddler from a deadly experiment.

Mills claims to have modelled Miss Fury on herself. She even named Marla’s cat Peri-Purr after her own beloved Persian pet. Born in Brooklyn in 1918, Mills grew up in a house headed by a single widowed mother, who supported the family by working in a beauty parlour. Mills worked her way through New York’s Pratt Institute by working as a model and fashion illustrator.

Censorship

In the end, ironically, it was Miss Fury’s high fashion wardrobe that became a major source of controversy.In 1947, no less than 37 newspapers declined to run a panel that featured one of Mills’ tough-minded heroines, Era – a South American Nazi-Fighter who became a post-war nightclub entertainer – dressed as Eve, replete with snake and apple, in a spangled, two-piece costume.

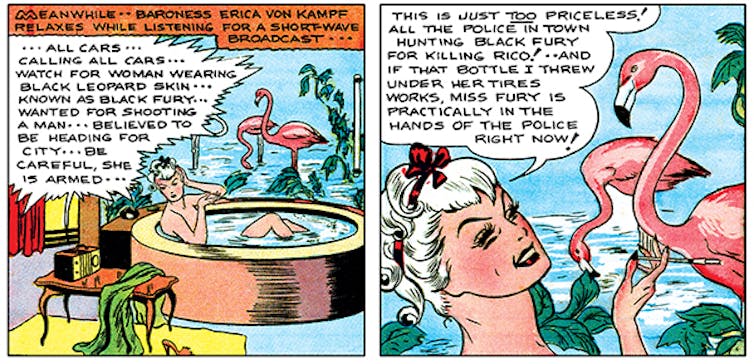

This was not the only time the comic strip was censored. Earlier in the decade, Timely comics had refused to run a picture of the villainess Erica resplendent in her bath – surrounded by pink flamingo wallpaper.

|

| Erica in the bath, surrounded by pink flamingo wallpaper. (Author provided.) |

In wartime, nations had relied on women to fill the production jobs that men had left behind. Just as “Rosie the Riveter” encouraged women to get to work with the slogan “We Can Do It!”, so too the comparative absence of men opened up room for less conventional images of women in the comics.

|

| A Miss Fury paper doll cut out. (Author provided) |

Miss Fury was dropped from circulation in December 1951, and despite a handful of attempted comebacks, Mills and her anarchic creation slipped from public view.

Mills continued to work as a commercial illustrator on the fringes of a booming advertising industry. In 1971, she turned a hand to romance comics, penning a seven-page story that was published by Marvel, but it wasn’t her forte. In 1979, she began work on a graphic novel Albino Jo, which remains unfinished.

Despite her chronic asthma, Mills – like the reckless Noir heroine she so resembled – chain-smoked to the bitter end. She died of emphysema on December 12, 1988, and is buried in New Jersey under the simple inscription, “Creator of Miss Fury”.

This year Mills’ work will be belatedly recognised. As a recipient of the 2019 Eisner Award, she will finally take her place in the Comics Hall of Fame, alongside the male creators of the Golden Age who have too long dominated the history of the genre. Hopefully this will bring her comic creation the kind of notoriety, readership and big screen adventures she thoroughly deserves.

About Today's Contributor:

Camilla Nelson, Associate Professor in Media, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.